8.1 KiB

| layout | title | parent | nav_order |

|---|---|---|---|

| default | GPU | Framework Concepts | 5 |

GPU

{: .no_toc }

- TOC {:toc}

Overview

MediaPipe supports calculator nodes for GPU compute and rendering, and allows combining multiple GPU nodes, as well as mixing them with CPU based calculator nodes. There exist several GPU APIs on mobile platforms (eg, OpenGL ES, Metal and Vulkan). MediaPipe does not attempt to offer a single cross-API GPU abstraction. Individual nodes can be written using different APIs, allowing them to take advantage of platform specific features when needed.

GPU support is essential for good performance on mobile platforms, especially for real-time video. MediaPipe enables developers to write GPU compatible calculators that support the use of GPU for:

- On-device real-time processing, not just batch processing

- Video rendering and effects, not just analysis

Below are the design principles for GPU support in MediaPipe

- GPU-based calculators should be able to occur anywhere in the graph, and not necessarily be used for on-screen rendering.

- Transfer of frame data from one GPU-based calculator to another should be fast, and not incur expensive copy operations.

- Transfer of frame data between CPU and GPU should be as efficient as the platform allows.

- Because different platforms may require different techniques for best performance, the API should allow flexibility in the way things are implemented behind the scenes.

- A calculator should be allowed maximum flexibility in using the GPU for all or part of its operation, combining it with the CPU if necessary.

OpenGL ES Support

MediaPipe supports OpenGL ES up to version 3.2 on Android/Linux and up to ES 3.0 on iOS. In addition, MediaPipe also supports Metal on iOS.

OpenGL ES 3.1 or greater is required (on Android/Linux systems) for running machine learning inference calculators and graphs.

MediaPipe allows graphs to run OpenGL in multiple GL contexts. For example, this can be very useful in graphs that combine a slower GPU inference path (eg, at 10 FPS) with a faster GPU rendering path (eg, at 30 FPS): since one GL context corresponds to one sequential command queue, using the same context for both tasks would reduce the rendering frame rate.

One challenge MediaPipe's use of multiple contexts solves is the ability to communicate across them. An example scenario is one with an input video that is sent to both the rendering and inferences paths, and rendering needs to have access to the latest output from inference.

An OpenGL context cannot be accessed by multiple threads at the same time. Furthermore, switching the active GL context on the same thread can be slow on some Android devices. Therefore, our approach is to have one dedicated thread per context. Each thread issues GL commands, building up a serial command queue on its context, which is then executed by the GPU asynchronously.

Life of a GPU Calculator

This section presents the basic structure of the Process method of a GPU

calculator derived from base class GlSimpleCalculator. The GPU calculator

LuminanceCalculator is shown as an example. The method

LuminanceCalculator::GlRender is called from GlSimpleCalculator::Process.

// Converts RGB images into luminance images, still stored in RGB format.

// See GlSimpleCalculator for inputs, outputs and input side packets.

class LuminanceCalculator : public GlSimpleCalculator {

public:

absl::Status GlSetup() override;

absl::Status GlRender(const GlTexture& src,

const GlTexture& dst) override;

absl::Status GlTeardown() override;

private:

GLuint program_ = 0;

GLint frame_;

};

REGISTER_CALCULATOR(LuminanceCalculator);

absl::Status LuminanceCalculator::GlRender(const GlTexture& src,

const GlTexture& dst) {

static const GLfloat square_vertices[] = {

-1.0f, -1.0f, // bottom left

1.0f, -1.0f, // bottom right

-1.0f, 1.0f, // top left

1.0f, 1.0f, // top right

};

static const GLfloat texture_vertices[] = {

0.0f, 0.0f, // bottom left

1.0f, 0.0f, // bottom right

0.0f, 1.0f, // top left

1.0f, 1.0f, // top right

};

// program

glUseProgram(program_);

glUniform1i(frame_, 1);

// vertex storage

GLuint vbo[2];

glGenBuffers(2, vbo);

GLuint vao;

glGenVertexArrays(1, &vao);

glBindVertexArray(vao);

// vbo 0

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, vbo[0]);

glBufferData(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, 4 * 2 * sizeof(GLfloat), square_vertices,

GL_STATIC_DRAW);

glEnableVertexAttribArray(ATTRIB_VERTEX);

glVertexAttribPointer(ATTRIB_VERTEX, 2, GL_FLOAT, 0, 0, nullptr);

// vbo 1

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, vbo[1]);

glBufferData(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, 4 * 2 * sizeof(GLfloat), texture_vertices,

GL_STATIC_DRAW);

glEnableVertexAttribArray(ATTRIB_TEXTURE_POSITION);

glVertexAttribPointer(ATTRIB_TEXTURE_POSITION, 2, GL_FLOAT, 0, 0, nullptr);

// draw

glDrawArrays(GL_TRIANGLE_STRIP, 0, 4);

// cleanup

glDisableVertexAttribArray(ATTRIB_VERTEX);

glDisableVertexAttribArray(ATTRIB_TEXTURE_POSITION);

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, 0);

glBindVertexArray(0);

glDeleteVertexArrays(1, &vao);

glDeleteBuffers(2, vbo);

return absl::OkStatus();

}

The design principles mentioned above have resulted in the following design choices for MediaPipe GPU support:

- We have a GPU data type, called

GpuBuffer, for representing image data, optimized for GPU usage. The exact contents of this data type are opaque and platform-specific. - A low-level API based on composition, where any calculator that wants to make use of the GPU creates and owns an instance of the

GlCalculatorHelperclass. This class offers a platform-agnostic API for managing the OpenGL context, setting up textures for inputs and outputs, etc. - A high-level API based on subclassing, where simple calculators implementing image filters subclass from

GlSimpleCalculatorand only need to override a couple of virtual methods with their specific OpenGL code, while the superclass takes care of all the plumbing. - Data that needs to be shared between all GPU-based calculators is provided as a external input that is implemented as a graph service and is managed by the

GlCalculatorHelperclass. - The combination of calculator-specific helpers and a shared graph service allows us great flexibility in managing the GPU resource: we can have a separate context per calculator, share a single context, share a lock or other synchronization primitives, etc. -- and all of this is managed by the helper and hidden from the individual calculators.

GpuBuffer to ImageFrame Converters

We provide two calculators called GpuBufferToImageFrameCalculator and ImageFrameToGpuBufferCalculator. These calculators convert between ImageFrame and GpuBuffer, allowing the construction of graphs that combine GPU and CPU calculators. They are supported on both iOS and Android

When possible, these calculators use platform-specific functionality to share data between the CPU and the GPU without copying.

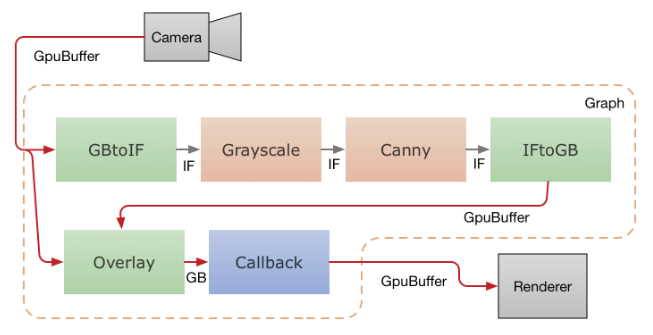

The below diagram shows the data flow in a mobile application that captures video from the camera, runs it through a MediaPipe graph, and renders the output on the screen in real time. The dashed line indicates which parts are inside the MediaPipe graph proper. This application runs a Canny edge-detection filter on the CPU using OpenCV, and overlays it on top of the original video using the GPU.

Video frames from the camera are fed into the graph as GpuBuffer packets. The

input stream is accessed by two calculators in parallel.

GpuBufferToImageFrameCalculator converts the buffer into an ImageFrame,

which is then sent through a grayscale converter and a canny filter (both based

on OpenCV and running on the CPU), whose output is then converted into a

GpuBuffer again. A multi-input GPU calculator, GlOverlayCalculator, takes as

input both the original GpuBuffer and the one coming out of the edge detector,

and overlays them using a shader. The output is then sent back to the

application using a callback calculator, and the application renders the image

to the screen using OpenGL.